History

Types like integers and rational numbers have existed in math for millennia. Some specifications that allowed users to create custom types and interface between them were developed in the 1960s. At the University of Oxford, Christopher Strachey detailed a polymorphic operator that applied to different types “without knowing their values.” This idea is commonly referred to as static polymorphism. He went on to mention an alternative that checks types dynamically similar to what we call dynamic polymorphism today. There is a record of this from “Fundamental Concepts in Programming Languages”. These were lecture notes released around 1967.

At the Norwegian computer center in Oslo, Ole-Johan Dahl and Kristen Nygaard released Simula 67, an event based programming language for simulation. The language introduced classes, inheritance, subclass, and virtual procedures. The language had coroutines, which allowed for “quasi-parallel” operation.

While in grad school at the University of Utah, Alan Kay coined the term object-oriented around 1967. His term came from biology. Each “cell” could be thought of as a virtual machine. In this model, processing data with different modules is done through message passing. He disliked the inheritance found in Simula. Instead, he favored dynamic typing. His view of building a system using a closed state, message based units can be seen as microservices.

At AT&T Bell Laboratories in New Jersey in 1979, Bjarne Stroustrup started developing a preprocessor program to convert “Simula-like classes to C”. Classes, inheritance, access control, constructors, and destructors were available features in 1980. Virtual functions were introduced in 1984. Cfront, Stroustrup’s early C++ compiler, introduced multiple inheritance in 1989. Around the same time, Andrew Koenig and Bjarne Stroustrup explain “resource acquisition is initialization” or RAII as a way of handling resources like locks when exceptions are thrown.

With many languages supporting various object oriented features, people started outlining best practices. In 1987, Barbara Liskov introduced the principle that substituting a child type for a sibling type shouldn’t break a parent type’s usage. Then, Bertrand Meyer mentioned the open-closed principle in “Object-Oriented Software Construction” in 1988. Next, Robert C Martin mentioned the interface segregation principle and dependency inversion principle in his Engineering Notebook columns for The C++ Report. Adding the single responsibility principle and tying other principles together, Robert C Martin outlined the SOLID principles in “Design Principles and Design Patterns” online in 2000.

James C. Dehnert and Alexander Stepanov introduced the idea of regular types in their 1998 paper titled “Fundamentals of Generic Programming”. These types had the following definitions: default constructor, copy constructor, destructor, assignment, equality, inequality, and ordering. In 2005, Scott Myers called this doing “as the ints do”: Effective C++, Third Edition. Later, this was extended to include the move constructor and move assigner. C++20 introduced the std::regular concept.

Overview

Object oriented programming is not as popular as it was. As with any programming language feature it can be abused. Multiple inheritance, long inheritance chains, and needless inheritance can add unnecessary complexity. There are few cases where it works well in C++: building product types, enforcing an invariant, and dynamic polymorphism. Generally, classes should follow one of these deliberately to follow the single responsibility principle, but there are exceptions.

Abuses of Object Oriented Programming

Overview

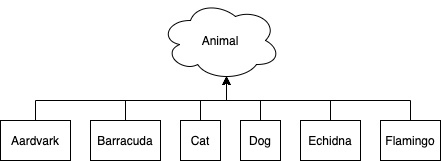

A lot of the bad object oriented programming practices are rooted in the education system. The biggest culprit is using the animal hierarchy example without context. For example, a cat and dog can inherit from an animal class as seen in the diagram above. Although it outlines the relationship between parts in an understandable way, it emphasizes a real world taxonomy that is irrelevant. Even though the analogy seems intuitive, it implicitly guides students down the wrong path. Programming should concern itself with data transformation and not taxonomy.

A lot of the bad object oriented programming practices are rooted in the education system. The biggest culprit is using the animal hierarchy example without context. For example, a cat and dog can inherit from an animal class as seen in the diagram above. Although it outlines the relationship between parts in an understandable way, it emphasizes a real world taxonomy that is irrelevant. Even though the analogy seems intuitive, it implicitly guides students down the wrong path. Programming should concern itself with data transformation and not taxonomy.

Older versions of Java has many mistakes in object-oriented programming. These problems occur due to deprecated techniques. Also, because it is so commonly used, there are many cases of misuse.

Multiple Inheritance

Java probably got it right by limiting inheritance. It allows for multiple inheritance for interfaces, but limits inheriting to only one abstract or concrete type.

There used to be cases where multiple inheritance helped define things in C++ like a class was not copyable. This feature could come in handy if the object was not copyable and needed to inherit some other interface. C++11 introduced =delete for special member functions, which is a clearer implementation.

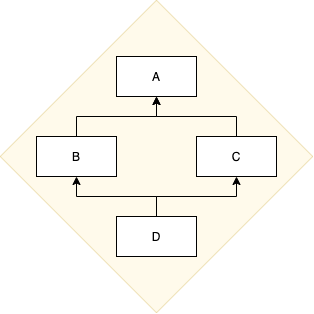

The other potential issue is the diamond problem. As seen above, the D class inherits from B and C. B and C each inherit from separately A. Since D inherits from two classes, it’s confusing whether A will come from B or C. If all the inheritance is public, B’s A and C’s A are included in D. There are mitigations, but it is best to avoid the issue.

Long Inheritance Chains

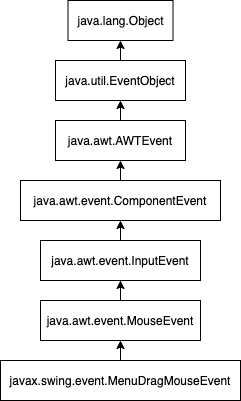

Generally, it’s best to avoid even a grandparent child class relationship. For example, Java took things too far with MenuDragMouseEvent. The chain is 5 long not counting the object class! Unless every interface and relationship between interfaces will be used, they shouldn’t be defined.

Inheriting Instead of Composing

Unfortunately, there’s been miscommunication that inheritance is for code reuse. Inheritance can help with testability and type compatibility, but composition is a better tool in general for code reuse.

Below is an example adapted from a Java tutorial. It has been converted to C++.

class Bicycle {

public:

Bicycle(int start_cadence, int start_gear, int start_speed)

: cadence_(start_cadence), gear_(start_gear), speed_(start_speed) {}

void SetCadence(int new_cadence) { cadence_ = new_cadence; }

void SetGear(int new_gear) { gear_ = new_gear; }

void ApplyBrake(int decrement) { speed_ -= decrement; }

void SpeedUp(int increment) { speed_ += increment; }

private:

int cadence_;

int gear_;

int speed_;

};

class MountainBike : public Bicycle {

public:

MountainBike(int start_cadence, int start_gear, int start_speed)

: Bicycle(start_cadence, start_gear, start_speed) {}

void SetHeight(int new_seat_height) { seat_height_ = new_seat_height; }

private:

int seat_height_;

};

There’s a lot of issues with the code above. It provides very little functionality over a tuple. Assuming that there really is a use for a bicycle data record and maybe a bicycle interface, it is better to depend on a minimal interface as opposed to depending on its implementation. Below is a rewrite to keep the data and implementation separate.

struct Bicycle2 {

int cadence;

int gear;

int speed;

};

struct MountainBike2 {

Bicycle2 bicycle;

int seat_height;

};

Bicycle2 ApplyBrake(const Bicycle2& bike, int decrement) {

return {.cadence = bike.cadence,

.gear = bike.gear,

.speed = bike.speed - decrement};

}

Bicycle2 SpeedUp(const Bicycle2& bike, int increment) {

return {.cadence = bike.cadence,

.gear = bike.gear,

.speed = bike.speed + increment};

}

In the code above, getting the Bicycle2 part of MountainBike2 could be done by using the dot operator. To do the same thing for inheritance, you would need a cast. It’s preferred to avoid casts even when implicit.

Note that ApplyBrake and SpeedUp are pure functions in that they don’t modify any instances. It’s arbitrary that ApplyBrake and SpeedUp are free functions. If they were const member functions, it would serve the same purpose. If unified function call syntax becomes part of the standard, the member and function versions could be called the same way.

Getters and Setters By Default

There are some good use cases of getters and setters, but it causes more harm than good when applied indiscriminately. Even boilerplate code can have bugs and needs to be read and tested. Some of the confusion was codified with MISRA C++ 2008’s Rule 11-0-1 stating that “Member data in non-POD class types shall be private.” Luckily, the C++ Core Guidelines recommends something more reasonable: avoid trivial getters and setters.

There’s some argument that getters and setters are good for providing some invariant later. That is false. If the invariant between the members of a class changes, then an interface should change. For example, if some values need to be range checked, they can be put in a trivial class that does it. If there is some thread safety that is necessary, the class or member data should be wrapped inside another class.

Good Usages of a Classes

Trivial Product Types

One of the easiest ways to return data is with a struct or tuple. Tuples are nameless by design. On the hand, structs name their types and fields. Having names is especially useful when calling an API from another file or when some of the fields share the same type. Unfortunately, the creator of C didn’t think to implement recursive equality for structs. Therefore, C++’s structs don’t have default comparison operators like tuples. Luckily, C++20 introduced default comparison’s by adding the following to the declaration publicly.

auto operator<=>(const Point&) const = default;

Equality and ordering complete the type making it what Dehnert and Stepanov call “regular”. Since the type will act like an int, users will be less surprised in its usage.

It is best to keep the type simple. Do this by keeping the data public, not inheriting, not defining special member functions, and keeping member functions const. Loosely speaking, types that are both trivial and use the standard layout are simple.

Dynamic Polymorphism

Classes may be the best solution for problems that require behavior to change at runtime where there are multiple abstract interfaces. For example, a user might read a config file to dynamically switch between functionality as seen below.

// Boilerplate from

// https://en.cppreference.com/w/cpp/utility/variant/visit

template <class... Ts>

struct overloaded : Ts... {

using Ts::operator()...;

};

template <class... Ts>

overloaded(Ts...) -> overloaded<Ts...>;

struct InputInterface {

virtual ~InputInterface() = default;

virtual std::string BlockingRead() = 0;

virtual std::string PollingRead() = 0;

};

class Serial : public InputInterface {

public:

Serial(const std::string& port);

virtual ~Serial() override;

private:

std::string BlockingRead() override;

std::string PollingRead() override;

};

class IPv4 : public InputInterface {

public:

IPv4(const std::string& address, const uint16_t port);

virtual ~IPv4() override;

private:

std::string BlockingRead() override;

std::string PollingRead() override;

};

struct SerialConfig {

std::string port;

};

struct IPv4Config {

std::string address;

uint16_t port;

};

using Config = std::variant<SerialConfig, IPv4Config>;

std::unique_ptr<InputInterface> MakeInput(const Config& config) {

return std::visit(

overloaded{

[](SerialConfig serial_config) -> std::unique_ptr<InputInterface> {

return std::make_unique<Serial>(serial_config.port);

},

[](IPv4Config ipv4_config) -> std::unique_ptr<InputInterface> {

return std::make_unique<IPv4>(ipv4_config.address,

ipv4_config.port);

}},

config);

}

void DoWork(const InputInterface& input_interface);

In the code above, there are two potential input types which can be configured at runtime. The MakeInput function can be thought of as a factory. This producer creates an instance in std::visit’s overloaded’s lambdas. The subtype is implicitly cast to the parent type. Then, the InputInterface is passed into DoWork. DoWork takes the parent type, InputInterface, as a parameter. The key feature is that DoWork can be tested separately. Assuming DoWork follows Liskov substitution principle, new input types can be added later.

The previous example has a lot of moving parts: a class interface, concrete class implementations, a factory method, and a do work function. Since the configuration capabilities are complex, the implementation is also complex. Every part is used and can be tested separately.

Enforcing an Invariant

Types can make certain inconsistencies unrepresentable at compile time. Depending on the language and the problem, it may be necessary to disallow certain inconsistencies at runtime. In C++, class initialization and access specification can enforce these qualities at runtime.

Values have certain preconditions before an operation and postconditions after the operation. In a future version of C++, there may be a specification called contracts to enforce that. Classes can do some part of the job in C++20 and earlier.

For example, we could enforce a value to be within a certain range. Otherwise, we crash and leave a message to the developer. A type like int8_t can be anything in [-128, 127]. But we might want to have a class to be sure the value has certain qualities.

template<typename T, T low, T high>

class BoundedInt {

public:

BoundedInt(const T value) {

assert(value >= low);

assert(value <= high);

value_ = value;

}

T operator()() const { return value_; }

private:

T value_;

};

In the code above, BoundedInt is a templated class that takes the low and high boundary values as well as the int type. The constructor uses those low and high values to check against the constructor argument at runtime. Then, a getter is used and the data is private so that the user cannot change the value without the check. Any consumer of BoundedInt will know that () will return a value in the range.

Resource Management

Finally, a great use of classes is for resource management. Basically, this means cleaning up something stateful and non-trivial to the system in the destructor. Resources can mean dynamic memory, locks, sockets, files, or other things. That way the object in scope will clean itself up when it exits scope. The technical term is “resource acquisition is initialization” or RAII.

A good example is C++20’s std::jthread. When it is constructed, it sets up a callback to be called on another thread. Then, when it exits scope, it calls join on its thread data. It provides a standard interface for acquiring a thread from a threading library and cleaning it up.

Combinations

Isolating the previous techniques and composing them is the preferred approach as opposed to large, unwieldy classes. But for certain problems mixing the techniques results in a better API.

Data structures in C++ typically enforce an invariant and perform resource management for performance. For example, a vector has internal variables that represent the size, which is the populated number of elements, and the capacity, which is the maximum number of elements that its memory block can hold. The invariant is that the size is always less than or equal to its capacity. Both are private variables so that users cannot break this relationship. The class also manages memory. When the instance exits the scope, the memory is freed.

Going back to the dynamic polymorphism example, it can be assumed that the class instances acquire some handles from the operating system or use some dynamic memory in their constructors. Then, in the implementation’s destructor, they destroy the handles and free the memory.

Conclusion

Classes are alive and well in C++. It’s not the only paradigm and their use cases are better understood through experience. It is often more powerful and convoluted than intended; but when used carefully, classes can elegantly solve today’s problems.

Source for Post