History

Random number generators have been relevant since the beginning of computers. Kendall and Babington-Smith created a machine to display light that flashed at random times in 1939. Alan Turing and Geoff Tootill designed the random number generator for the Manchester Mark 1. While working in UC Berkeley’s mathematics department, D. H. Lehmer presented on the linear congruential generator in 1949. In 1955, the RAND corporation published A Million Random Digits and 100,000 Normal Deviates.

Later, C’s rand function became part of the C89 standard. Makoto Matsumoto and Takuji Nishimura published a paper to the ACM on the Mersenne Twister. Then, Jens Maurer added the random number library to boost 1.15.0 in 2000. Finally, In 2011 the random header was added to C++11, which will be discussed further.

Uses

From the entertainment side, random numbers are used for games like gambling or video games. The surprising interactions can be exciting. From a more practical side, it can also be used for cryptography. Cryptography is essential for banking. It facilitates authentication and privacy. I’m most interested in random number generators used in robotics.

Often the algorithms using random number generators are called sampling based methods, as in sampling a probability distribution, or Monte Carlo methods named after a popular gambling destination in Europe. These methods can be applied to localization. The localization problem in robotics answers the question of where something is. One of the most efficient, robust, and easy to implement algorithms is Monte Carlo Localization (MCL) or a Particle Filter. Typically, the algorithm starts by instantiating particles uniformly inside an expected location. The algorithm has a motion update and a sensor update. During the motion update, the particles propagate in time based on their state and their certainty reduces. During the sensor update, the particles are evaluated on how well they match the sensor measurement. Then, the particles are resampled. This algorithm is great, because it is multi-model, which means that it can track many very different guesses. Even if the guesses are very different for some time, they typically converge to one guess quickly. Here a guess is a particle. In the image below a robot is moving with a lidar to determine where it is in a mapped area.

Another great problem that sampling based methods can be applied to is planning. In robotics, planning determines how to get from one state to another. Determining how to get from one side of a room to another or how to move one’s body to pick something up are examples of motion planning problems. Rapidly-Exploring Random Tree (RRT) is an algorithm that samples many trajectories to get from one state to another. Like the particle filter, the algorithm is extremely simple. It merely gets a valid, random state; finds the nearest neighbor from the tree; selects the input from the nearest state to the random state; and if the transition is valid, the new state and transition are added to the tree. The end criteria can be a set number of iterations or closeness to a connection to the goal state. This algorithm is great at finding feasible solutions quickly, although it does not guarantee optimality. In the video below the initial state is yellow, the obstacles are red, the goal state is magenta, the RRT being generated is light green, and the output trajectory is the red line segments.

std::random Overview

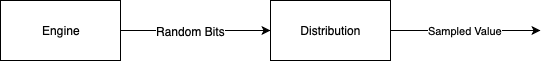

C++ standardized its random number generator library accessed via the random header. It is organized into engines and distributions. Engines generate random bits. This process can be done via a mathematical function that is statistically random or physically. One example of a physical source of random numbers is an avalanche diode circuit. A std::distribution is a probability distribution. Popular distributions include their uniform distribution, which can model rolling a dice, and the normal distribution, which can model height among an animal population. In the image below the engine passes random bits to the distribution, which returns a sampled value to the user.

Why Not Use cstdlib’s rand Function?

C’s rand function has been used for many decades. For some applications on some platforms it may still be useful. The following properties are implementation defined.

- performance

- entropy source

- thread safety

- max value

It’s assumed that rand returns a uniformly random number. Often developers seed with srand(time(0)); expecting new results every time. Unfortunately, the time function is often implemented to have a resolution of seconds so two programs started around the same time can have the same seed.

On some platforms rand is implemented as a linear congruential generator. This function is fast and does not take much memory. Unfortunately, because the state is so small, the results can be predicted easier than other engines. Depending on the implementation, it may repeat after some time.

Why Not Just Mod Random Bits to Get a Uniform Distribution?

rand returns a value from 0 and RAND_MAX, which is implementation defined. It is rare that rand’s range is divisible by the desired uniform distribution’s range. In these cases, certain parts of the distribution are more likely than others making the distribution not strictly uniform.

std::random Common Engines

Here are 4 common engines

- default random engine

- minstd rand

- mt19937

- random device

The default random engine is meant to be used when the details don’t matter for the application or platform. With the default random engine any engine may be used. minstd rand is a parameterized linear congruential engine. The linear congruential generator as stated before has less state, but is the most predictable. mt19937 is a parameterized mersenne twister engine. It stores a lot of state, but can be used over time with a high level of predictability. It’s not cryptographically secure, because there are programs that can predict its values. The random device engine may take advantage of physical hardware to avoid determinism. This lack of determinism may take time for the device to acquire more entropy. Note that the standard allows for a deterministic implementation for the random device engine like the other engines above, if the hardware source is unavailable. This comparison is summarized in the table below.

| Engine | Deterministic | Speed | State | Predictability |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| default random engine | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a |

| linear congruential engine | Yes | Very Fast | Small | Very High |

| mt19937 | Yes | Fast | Large | High |

| random device | No | Slow | Small | Low |

std::random Common Distributions

Here are some common distributions

- normal distribution

- uniform int distribution

- uniform real distribution

The normal distribution or Gaussian distribution takes a real value like a double or float and returns a value based on a mean and standard deviation. There are separate classes for integer and real uniform distributions. Any value in their range is equally likely. It is important to note that the integer version takes bounds parameters [min, max], while the real version takes bounds parameters [min, max). It’s defined this way so that a 32-bit uniform_int_distribution can have bounds parameters that are also 32-bit.

Example Usage

Now that we have an engine and a distribution, let’s write some code to put it together. The following code was modified from a video. The default random engine was chosen, because people often can’t tell the difference in random number generators. To produce different results every time the program is run, the default random engine is seeded with some random bits from the random device. Then, the uniform int distribution is used, because it models the outcome of a dice roll.

int RollDie() {

static std::random_device r;

static std::default_random_engine e(r());

static std::uniform_int_distribution<int> d(1, 6);

return d(e);

}

Note that random device, default random engine, and uniform int distribution are static. static is used as an optimization so that the objects are not constructed each time. In the case of mt19937, putting its large state on the stack every time the function is called may take too long. Distributions are fast to construct.

Benchmarks

To better understand the library, it has been tested directly. The timing, a statistic, object size, and program size has been examined. The following benchmarks were tested on my 2012 MacBook pro. It runs Mac 10.14.3 and has a 2.7 GHz Intel Core i7. The compiler version is

g++ --version 01:33:52

Configured with: --prefix=/Applications/Xcode.app/Contents/Developer/usr --with-gxx-include-dir=/usr/include/c++/4.2.1

Apple LLVM version 10.0.0 (clang-1000.11.45.5)

Target: x86_64-apple-darwin18.2.0

Thread model: posix

InstalledDir: /Applications/Xcode.app/Contents/Developer/Toolchains/XcodeDefault.xctoolchain/usr/bin

The following code was used to compute the timings and compute the difference between the arithmetic mean and the expected value. It was compiled with g++ -std=c++14 -O3 -Wall -Wextra -pedantic file.cc.

Engine Affect on Program

Engines have different sizes and can affect binary size. The following programs were used to evaluate object size and program size. The random engine was used to seed the various engines to prevent optimization from doing everything at compile time.

random_default_random_engine.cc

#include <cstdlib>

#include <iostream>

#include <random>

int main() {

std::random_device rd;

std::default_random_engine e(rd());

std::cout << "sizeof = " << sizeof(e) << std::endl;

std::cout << e() << std::endl;

return EXIT_SUCCESS;

}

random_minstd_rand.cc

#include <cstdlib>

#include <iostream>

#include <random>

int main() {

std::random_device rd;

std::minstd_rand e(rd());

std::cout << "sizeof = " << sizeof(e) << std::endl;

std::cout << e() << std::endl;

return EXIT_SUCCESS;

}

random_mt19937.cc

#include <cstdlib>

#include <iostream>

#include <random>

int main() {

std::random_device rd;

std::mt19937 e(rd());

std::cout << sizeof(e) << std::endl;

std::cout << e() << std::endl;

return EXIT_SUCCESS;

}

random_random_device.cc

#include <cstdlib>

#include <iostream>

#include <random>

int main() {

std::random_device e;

std::cout << "sizeof = " << sizeof(e) << std::endl;

std::cout << e() << std::endl;

return EXIT_SUCCESS;

}

random_rand.cc

#include <cstdlib>

#include <iostream>

#include <random>

int main() {

std::random_device rd;

std::srand(rd());

std::cout << std::rand() << std::endl;

return EXIT_SUCCESS;

}

See the table below. mt19937 is a much larger object than the other engines. Somehow the program size of the mt19937 is slightly lower than the other engines. This is strange, because the random device engine by itself is less code. C’s rand function produces the smallest binary. Based on the object size of the default random engine, it is actually minstd rand.

| Engine | Program Size (Kilobytes) | Object Size (Bytes) |

| C rand | 9.7 | n/a |

| default random engine | 11 | 4 |

| minstd rand | 11 | 4 |

| mt19937 | 9.8 | 2504 |

| random device | 11 | 4 |

Uniform Distribution with Various Engines

Different engines have different performance characteristics. The code below was used to compare time and a simple, statistical property.

random_benchmark.cc

#include <cstdlib>

#include <functional>

#include <iostream>

#include <map>

#include <random>

#include <string>

#include <vector>

using std::function;

using std::map;

using std::string;

using std::vector;

using results_type =

map<string, std::pair<std::chrono::nanoseconds, vector<int>>>;

template <class Engine> int get_int(const int min, const int max) {

static Engine e;

static std::uniform_int_distribution<int> d(min, max);

return d(e);

}

map<string, function<int()>> get_engines(const int min, const int max) {

return {

{"rand with mod",

[min, max]() { return min + (std::rand() % (max - min + 1)); }},

{"default_random_engine",

[min, max]() { return get_int<std::default_random_engine>(min, max); }},

{"minstd_rand",

[min, max]() { return get_int<std::minstd_rand>(min, max); }},

{"mt19937", [min, max]() { return get_int<std::mt19937>(min, max); }},

{"random_device",

[min, max]() { return get_int<std::random_device>(min, max); }}};

}

results_type compute_results(const map<string, function<int()>> &engines,

const int min, const int max,

const int iterations) {

results_type results;

for (const auto &engine : engines) {

vector<int> result(max - min + 1, 0);

const auto start = std::chrono::steady_clock::now();

for (int i = 0; i < iterations; ++i) {

const int rand_value = engine.second();

const int result_index = rand_value - min;

++result[result_index];

}

const auto diff = std::chrono::steady_clock::now() - start;

const auto timed_result = std::make_pair(diff, result);

results.emplace(engine.first, timed_result);

}

return results;

}

void print_results(const results_type &results, const int min,

const int iterations) {

for (const auto &result : results) {

std::cout << result.first << ", ";

}

for (auto result = results.begin(); result != results.end(); ++result) {

std::cout << result->first;

if (std::next(result) != results.end()) {

std::cout << ", ";

} else {

std::cout << '\n';

}

}

for (const auto &result : results) {

const auto seconds =

std::chrono::duration<double>(result.second.first).count();

std::cout << seconds << ", ";

}

for (auto result = results.begin(); result != results.end(); ++result) {

double sum = 0.0;

const vector<int> &data = result->second.second;

for (vector<int>::size_type i = 0U; i < data.size(); ++i) {

sum += data[i] * (static_cast<double>(min) + i);

}

std::cout << sum / iterations;

if (std::next(result) != results.end()) {

std::cout << ", ";

} else {

std::cout << '\n';

}

}

}

int main() {

constexpr int kIterations = 100;

constexpr int kMin = -5;

constexpr int kMax = 5;

const map<string, function<int()>> engines(get_engines(kMin, kMax));

const results_type results(compute_results(engines, kMin, kMax, kIterations));

print_results(results, kMin, kIterations);

return EXIT_SUCCESS;

}

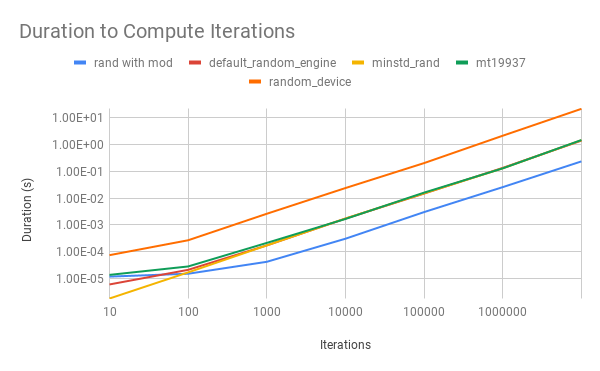

The timing the biggest differentiator. See the plot below. The default random engine was much slower than minstd rand and mt19937 and those were much slower than rand with mod. It’s interesting that rand with mod was so fast, because it should be very similar to minstd rand. One explanation is that the distribution class may be calling the minstd rand engine multiple times.

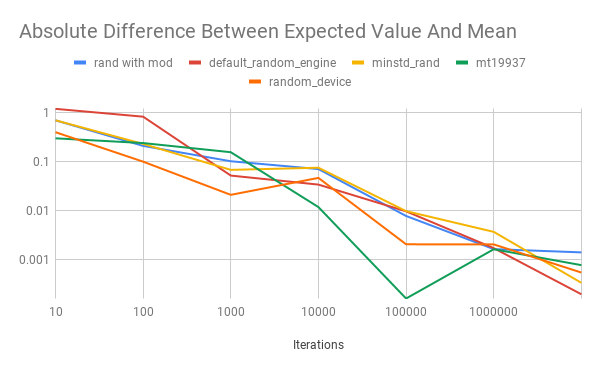

Next, the absolute value of the difference between the expected value and the arithmetic mean was compared. This metric was meant to be a simple, statistical check on how the engines affect the distribution. As seen in the plot below, the engines don’t appear to affect the result of the distribution. Even rand with modulo’s generates results that seem statistically usable even though it should have sampled lower numbers more frequently.