Overview

There are a lot of ways to implement code. Here are a few negative patterns that I’ve seen or made the mistake of following over the years.

1. Branching for Mathematical Functions

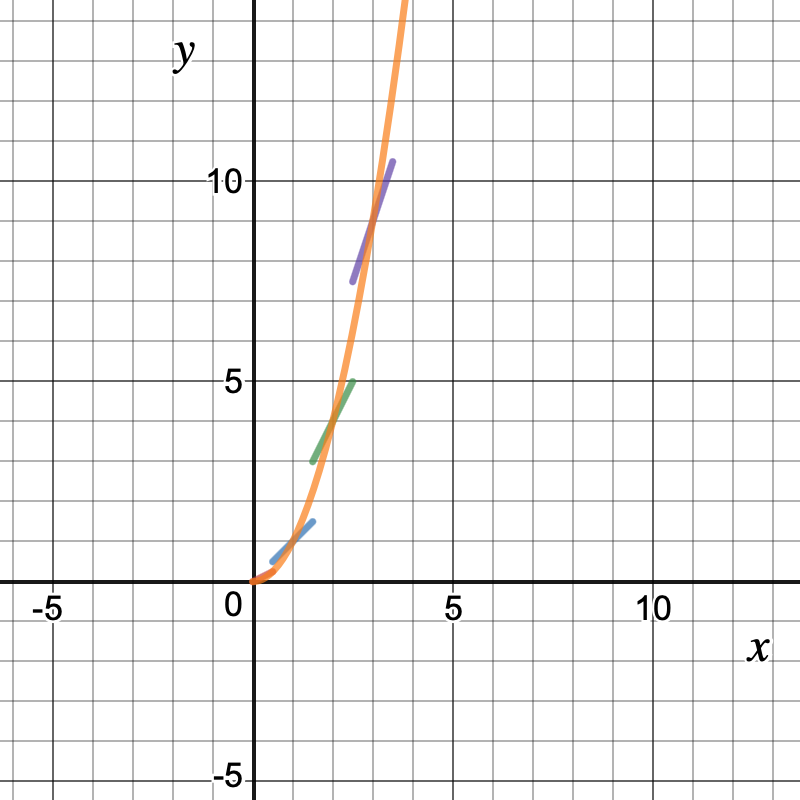

1.a. Piecewise Linear Function for a Continuous Polynomial

Often, when a value is a bit off, a fudge factor is added. Sometimes, this factor is a polynomial function. Without taking a step back to simplify things, the code may end up being a bunch of if statements. See the example below.

if (a>0&&a<0.5) {

a *= 0.5;

} else if (a>=1.5 && a<2.5) {

a *= 2;

} else if (a>=2.5 && a<3.5) {

a *= 4;

}

Assuming the domain is in [0, 3), the function could be approximated as

a *= a;

The difference in values can be seen in the image above. The approximation is in orange. Assuming the approximation is acceptable, this representation is more maintainable.

1.b. Case Statement for Linear Function

Here’s another example, where a common mathematical function could replace a branch expression.

void Rotate(int a, Rotatable *const r) {

switch (a) {

case 0:

r->Rotate(M_PI / 8);

break;

case 1:

r->Rotate(M_PI / 4);

break;

case 2:

r->Rotate(3 * M_PI / 8);

break;

case 3:

r->Rotate(M_PI / 2);

break;

}

}

Instead, the case statement could be replaced with the following.

void Rotate(int a, Rotatable *const r) {

r->Rotate(a * M_PI / 8);

}

The above code takes the integer used to branch and operates on it directly.

2. Parent Classes Knowing All of the Subclasses

To not repeat yourself, avoid mixing enumerations and subtypes.

class Parent {

public:

enum class Type { A, B };

Parent(Type type) : type_(type) {}

void Foo() {

switch (type_) {

case Type::A:

std::cout << "ChildA";

break;

case Type::B:

std::cout << "ChildB";

break;

}

}

private:

Type type_;

};

class ChildA : public Parent {

public:

ChildA() : Parent(Parent::Type::A) {}

};

class ChildB : public Parent {

public:

ChildB() : Parent(Parent::Type::B) {}

};

In the example above the parent class has to be aware of each subclass. A better design would be to extend the class without having to modify the parent.

class Parent {

public:

Parent();

virtual void Foo() = 0;

};

class ChildA : public Parent {

public:

void Foo() override { std::cout << "ChildA\n"; };

};

class ChildB : public Parent {

public:

void Foo() override { std::cout << "ChildB\n"; };

};

The above example would look the same for a Foo caller on a Parent type. The Parent class doesn’t need to encode each type. The types encode the functionality.

This example is a generality. Due to C++’s lack of reflection, some redundancy might be necessary to serialize.

3. Global Mutable State

System calls are expected to change state. For example, receiving network packets, generating a random number, receiving mouse events might change global state. These are necessary for functionality.

C++ makes it too easy to write global variables. It is the default behavior of defining a variable outside of a function or class. Python is saner in that it makes the user write global when the variable is used. Some libraries like gflags make it too easy to write globals. See the example below.

int a_global = 0;

DEFINE_int32(another_global, 0, "another global variable");

void Foo() {

++a_global;

++FLAGS_another_global;

}

void Bar() {

std::cout << "I see " << a_global << " " << FLAGS_another_global << '\n';

}

int main() {

Foo();

Bar();

return EXIT_SUCCESS;

}

Here’s an alternative with a tighter scope.

DEFINE_int32(carefully_used_global, 0, "carefully used global variable");

struct FooRet {

int val_0;

int val_1;

};

FooRet Foo(const int val_0, const int val_1) { return {val_0 + 1, val_1 + 1}; }

void Bar(const int val_0, const int val_1) {

std::cout << "I see " << val_0 << " " << val_1 << '\n';

}

int main() {

const FooRet foo_ret = Foo(0, FLAGS_carefully_used_global);

Bar(foo_ret.val_0, foo_ret.val_1);

return EXIT_SUCCESS;

}

In the example above, the gflags library was kept in. Even though the variable is global, the usage is careful only to read from it.

For moving data around, mutating global state is very hard to reason about. Unless there are specific performance or functionality reasons, it should be avoided.

4. Wrapping Standard Containers But Providing the Same Functionality

A lot of libraries end up wrapping STL containers in a class with no additional benefit. There are reasons to replace or extend containers. For example, adding constexpr support for containers. Sometimes the performance, ease of debugging, and exception requirements could be improved in the standard implementation like in EASTL. For some developers, the performance and the security of hash tables are important. Swiss tables addresses this need.

The interface for a container implementation is often sufficient. Reimplementing an interface may be good for personal practice, but provides no benefit in production.

struct Book {

std::string title;

int id;

};

class Library {

public:

void AddBook(const Book& book) { books_.push_back(book); }

Book& GetBookByIndex(const int i) { return books_[i]; }

private:

std::vector<Book> books_;

};

The above code is a naive implementation of std::vector’s interfaces. Assuming the “Library” word is really necessary, it would be better to replace the Library class with a using directive. See below.

struct Book {

std::string title;

int id;

};

using Library = std::vector<Book>;

It’s worth learning the standard collections that are a part of the language. C++ has been widely available since 1994, but adoption was slow.

It’s safe to assume that the API user knows the standard collection API. If they do not, it is well documented.

5. Large Classes, Functions, or Files

There’s a lot of talk about different programming styles. Style is often much less of an issue in comparison to giant classes, functions, or files.

Enforcing a hard limit is probably not the right answer. A good rule of thumb is if the function or method is within an editor window length. For classes and files, a rule of thumb is less than 1000 lines.

This is an art. Breaking down solutions into understandable chunks is important for a group of engineers to work together.

6. Abstract Classes

Whenever I see an abstract interface, I think composition over inheritance. There may be legitimate uses of abstract classes, but typically the implementations are better broken out. Reusing code through functions improves readability and testability. See the example below.

class Parent {

protected:

int Foo() { return count_++; }

private:

int count_ = 0;

};

class Child : Parent {

public:

int Bar() { return Foo() + 1; }

};

Instead of above, it would be better to encapsulate the parent class instead of inherit from it as seen below.

class StandaloneClass {

public:

int Foo() { return count_++; }

private:

int count_ = 0;

};

class MyClass {

public:

int Bar() { return s_.Foo() + 1; }

private:

StandaloneClass s_;

};

Note that in the first code snippet the Foo method was protected. In the second Example, it must be public. This visibility change is good, because the encapsulated instance, s_, is private.

Abstract classes used to be used for things like disabling the copy constructor. Nowadays, they complicate code.

Conclusion

These examples were taken from my experience. They are toy problems in isolation, but they appear in code bases all over. It’s difficult to write simple code, but it helps for readability.

Source for Post